Overview

Diabetes Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee

Loren D. Grossman MD, FRCPC, FACP, Robert Roscoe BScPharm, ACPR, CDE, CPT, Anita R. Shack BFA, DC, FATA

Anchored List of chapter sections

- Key Messages

- Key Messages for People with Diabetes

- Introduction

- NHP for the Prevention and Treatment of Diabetes and Its Complications

- NHP for the Prevention and Treatment of Diabetes

- NHP for the Treatment of the Co-Morbidities and Complications of Diabetes

- Adverse Effects

- Other Complementary and Alternative Approaches for the Prevention and Treatment of Diabetes and Its Complications

- Yoga

- Traditional Chinese Medicine

- Manual Therapies

- Other Relevant Guidelines

- Author Disclosures

1. Key Messages

- Anywhere from 25% to 57% of people with diabetes report using complementary or alternative medicine.

- Some natural health products have shown a lowering of A1C by ≥0.5% in trials lasting at least 3 months in adults with type 2 diabetes, but most are single, small trials that require further large-scale evaluations before they can be recommended for widespread use in diabetes.

- A few more commonly used natural health products for diabetes have been studied in larger randomized controlled trials and/or meta-analyses refuting the popular belief of benefit of these compounds.

- Health-care providers should always ask about the use of complementary and alternative medicine as some may result in unexpected side effects and/or interactions with traditional pharmacotherapies.

2. Key Messages for People with Diabetes

- Many people with diabetes use complementary medicine (along with) or alternative medicine (instead of) with conventional medications for diabetes.

- Although some of these therapies may have the potential to be effective, they have not been sufficiently studied and others can be ineffective or even harmful.

- It is important to let your health-care providers know if you are using complementary and/or alternative medicine for your diabetes.

3. Introduction

Despite advances in the management of type 1 and type 2 diabetes, therapeutic targets are often not met. People dissatisfied with conventional medicine often turn to nontraditional alternatives. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) can be loosely defined as health-care approaches developed outside of mainstream Western, or conventional medicine, with “complementary” meaning used together with, and “alternative” meaning used in place of conventional medicine (1). According to a report from the Fraser Institute, 50% to 79% of Canadians had used at least 1 CAM sometime in their lives, based on surveys from 1997, 2006 and 2016 (2). The most common types used in 2016 were massage (44%), chiropractic care (42%), yoga (27%), relaxation techniques (25%) and acupuncture (22%). According to the United States 2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), 17.7% of American adults used a dietary supplement other than vitamins and minerals (3). A few surveys have sought to characterize the use of CAM in persons with diabetes. In a Canadian study of 502 people with diabetes, 44% were taking over-the-counter supplements with 31% taking alternative medications (4). A United States national survey reported 57% of those with diabetes using CAM in the previous year (5). The Medical Expenditure Panel Surveys (MEPS) showed that those with diabetes were 1.6 times more likely to use CAM than those without diabetes, with older age (≥65 years) and higher educational attainment (high school education or higher) independently associated with CAM use (6). An Australian study reported 25% of people with diabetes stated they had used CAM within the previous 5 years (7).

This chapter will review CAM, including natural health products (NHP) and others, such as yoga, acupuncture, tai chi and reflexology, that have been studied for the prevention and treatment of diabetes and its complications.

4. NHP for the Prevention and Treatment of Diabetes and Its Complications

In Canada, NHP are defined as vitamins and minerals, herbal remedies, homeopathic medicines, traditional medicines, such as traditional Chinese medicines, probiotics, and other products like amino acids and essential fatty acids (8). They are regulated under the Natural Health Products Regulations, which came into effect in 2004. In general, the current level of evidence for the efficacy and safety of NHP in people with diabetes is lower than that for pharmaceutical agents. Trials tend to be of shorter duration and involve smaller sample sizes. Concerns remain about standardization and purity of available compounds, including their contamination with regular medications and, in some cases, toxic substances (9–11). Various NHP have been studied to evaluate their impact on the development of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, glycemic control in people with diabetes, and on the various complications of diabetes.

5. NHP for the Prevention and Treatment of Diabetes

A number of immune modulators have been studied in an attempt to prevent or arrest beta cell decline in type 1 diabetes, most with limited success. A few NHP have also been studied in this regard. A randomized controlled trial of people with new-onset type 1 diabetes assessed the effect of vitamin D supplementation on regulatory T (Treg) cells (12). After 12 months, Treg suppressive capacity was improved, although there was no significant reduction in C-peptide decline. Observational studies have suggested an inverse relationship between vitamin D levels and the development of type 2 diabetes (13), although randomized controlled trials are lacking (14). In the large, prospective cohort study, The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY), early probiotic supplementation may reduce the risk of islet autoimmunity in children at the highest genetic risk of type 1 diabetes (15).

A number of NHP have been evaluated to assess their effect on the progression from impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) to diabetes. Tianqi is a traditional Chinese medicine consisting of 10 different herbs. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 12 months duration, Tianqi was shown to reduce the progression from IGT to type 2 diabetes by 32% (16). A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies of omega-3 fatty acids or fish intake showed that an increased intake of alpha linoleic acid (ALA) and fatty fish reduced the risk of type 2 diabetes significantly with ALA, only in Asians (17). In a randomized controlled trial, the traditional Chinese medicine Shenzhu Tiaopi granule (SZTP) significantly reduced the conversion from IGT to type 2 diabetes to 8.52% from 15.28% with placebo, with a significantly higher number of people with IGT reverting to normal blood glucose levels as well (42.15% vs. 32.87% for placebo) (18).

In adults with type 2 diabetes, the following NHP have been shown to lower glycated hemoglobin (A1C) by at least 0.5% in randomized controlled trials lasting at least 3 months:

- Ayurveda polyherbal formulation (19)

- Citrullus colocynthis (20)

- Coccinia cordifolia (21)

- Eicosapentaenoic acid (22)

- Ganoderma lucidum (23)

- Ginger (Zingiber officinale) (24)

- Gynostemma pentaphyllum (25)

- Hintonia latiflora (26)

- Lichen genus Cladonia BAFS “Yagel-Detox” (27)

- Marine collagen peptides (28)

- Nettle (Urtica dioica) (29)

- Oral aloe vera (10)

- Pterocarpus marsupium (vijayasar) (30)

- Salacia reticulata (31)

- Scoparia dulcis porridge (32)

- Silymarin (33,34)

- Soybean-derived pinitol extract (35)

- Touchi soybean extract (36)

- Traditional Chinese medicine herbs:

- Trigonella foenum-graecum (fenugreek) (46,47)

These products are promising and merit consideration and further research, but, as they are mostly single, small trials or meta-analyses of such, it is premature to recommend their widespread use.

The following NHP either failed to lower A1C by 0.5% in trials lasting at least 3 months in adults with type 2 diabetes, or were studied in trials of shorter duration, nonrandomized or uncontrolled:

- Agaricus blazei (48)

- American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius L.) (49)

- Antioxidants: (fruit/vegetable extract) (50), (pomegranate extract) (51)

- Camellia sinensis (52)

- Flaxseed oil (53)

- French maritime pine bark (54)

- Ginseng (55,56)

- Juglans regia extract (57)

- Liuwei Dihuang Pills (LDP) (58)

- Momordica charantia (bitter melon or bitter gourd) (59,60)

- Rosa canina L. (rose hip) (61)

- Salvia officinalis (62)

- Soy phytoestrogens (63)

- Tinospora cordifolia (64)

- Tinospora crispa (65)

- Vitamin C (66–68)

- Vitamin E (69–73)

The following NHP have demonstrated conflicting effects on A1C in trials lasting at least 3 months in adults with type 2 diabetes:

- Cinnamon (74–79)

- Coenzyme Q10 (80–83,85,86)

- Ipomoea batatas (caiapo) (87,88)

- L-carnitine (89–92)

- Magnesium (93–99)

- Omega 3 fatty acids (100,101)

- Probiotics (102,103)

- Zinc (104,105)

A few products, such as chromium, vitamin D and vanadium, have been the subjects of special interest in diabetes.

Chromium is an essential trace element involved in glucose and lipid metabolism. Early studies revealed that chromium deficiency could lead to IGT, which was reversible with chromium repletion. This led to a hypothesis that chromium supplementation, in those with both adequate and deficient chromium stores, could lead to improved glucose control in people with diabetes (106,107). Indeed, an analysis of the large NHANES database showed that, in those in the general population who reported consuming a chromium supplement, the odds of developing diabetes was 19% to 27% lower than those not taking a chromium supplement (108). However, randomized controlled studies of chromium supplementation have had conflicting results, with most showing no benefit on improving A1C (109–121), although some showed an improved fasting glucose level (120,121). Most were small studies, of short duration, and some not double-blinded. More recent meta-analyses have also reported conflicting results, with some concluding no benefit of chromium on reducing A1C, lipids or body weight in people with diabetes (122), and others reporting some benefit depending upon the dose and formulation consumed (84). The later meta-analysis reported marked heterogeneity and publication bias in the included studies.

Vitamin D has received much interest recently with purported benefits on cardiovascular disease (CVD), cancer and diabetes. Randomized controlled trials have not demonstrated a benefit of vitamin D supplementation on glycemic control in diabetes (123–138), further confirmed by meta-analyses (139,140).

Vanadium, a trace element that is commonly used to treat type 2 diabetes, has not been studied in randomized controlled trials evaluating glycemic control by A1C over a period of 3 months or longer.

6. NHP for the Treatment of the Co-Morbidities and Complications of Diabetes

A number of NHP have been evaluated for the various co-morbidities and complications of diabetes, including lipids and blood pressure (BP) in diabetes, as well as CVD, nephropathy, retinopathy and peripheral neuropathy. As with the studies of glycemic control, most had small sample sizes and meta-analyses had marked heterogeneity of included studies, making strong conclusions difficult.

Randomized controlled trials demonstrating a benefit on lipid parameters in diabetes include: Ayurvedic polyherbal formulation (19), Hintonia latiflora (26)and magnesium (99). In postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes, vitamin D supplementation for 6 months reduced serum triglycerides (TG) without effect on other lipid parameters (141), while a meta-analysis with high heterogeneity showed benefit on lowering total cholesterol and TG (142). Other studies have failed to show significant benefit of vitamin D supplementation on lipids in people with diabetes (130,137,143). A meta-analysis of Berberine showed it to reduce TG and increase high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) more than traditional lipid-lowering drugs, with no difference on total or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) (37). Berberine was also shown to reduce total and LDL-C and increase HDL-C combined with traditional lipid-lowering drugs compared with those drugs alone.

Randomized controlled trials demonstrating a benefit on systolic and/or diastolic BP include: magnesium (99), American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius L.) (49) and Purslane extract (Portulaca oleracea L.) (144). Berberine when combined with traditional BP medications can lower systolic BP by an additional 4.9 mmHg and diastolic BP by 2 mmHg, but not when compared with traditional antihypertensive medications alone (37). In 1 meta-analysis, vitamin D was shown to reduce BP by a statistically significant, but not clinically meaningful amount (145).

Ethylene diamine tetra-acetic (EDTA) acid chelation therapy has been postulated to have a number of cardiovascular (CV) benefits. A large randomized controlled trial (Trial to Assess Chelation Therapy—TACT) showed a modest benefit of an 18% risk reduction for a composite of CV complications in people with a recent myocardial infarct (146). A pre-specified subanalysis of people with diabetes showed a more robust 39% to 41% risk reduction in the primary endpoint out to 5-years follow up (147).

The traditional Chinese medicine product, The Compound Danshen Dripping Pill (CDDP), consisting of 3 herbal preparations, was evaluated in a randomized controlled trial of 24 weeks duration, for its effect on the progression of diabetic retinopathy (148). Using a nonstandardized method of grading fluorescence fundal angiography, higher doses of CDDP were found to delay the progression of diabetic retinopathy.

A number of NHP have been reported to improve diabetic nephropathy. However, there is variation in the definition of diabetic nephropathy in the various studies, with many assessing urinary albumin excretion (UAE) and/or 24-hour urine protein excretion without a confirmatory diagnosis. Many are of short duration, some without reporting an assessment of renal function or its progression, or with conflicting results on the various measures. Some products showing a reduction in UAE in people with diabetes include: the traditional Chinese medicines Yiqi Huayu, Yiqi Yangyin (149), Qidan Dihuang Grain (150), and Jiangzhuo (SKC-YJ) (151), Huangshukuihua (Flos Abelmoschi Manihot) (152,153), Pueraria lobata (gegen, puerarin) (154), Tangshen Formula (155), Zishentongluo (ZSTL) (45), vitamin D (156), and vitamin D analogue paricalcitol in type 1 diabetes (157).

A number of NHP have been reported to improve diabetic peripheral neuropathy, as assessed by pain scores and/or nerve conduction studies (NCS). Topical Citrullus colocynthis (bitter apple) extract oil was studied in a small randomized controlled trial in people with painful diabetic polyneuropathy (158). After 3 months, there was a significantly greater decrease in mean pain score and improvement in nerve conduction velocities compared with placebo. A meta-analysis of puerarin in diabetic peripheral neuropathy reported benefits in pain scores and NCS (159). In a small randomized controlled trial, the traditional Chinese medicine MHGWT showed reduced pain scores compared with placebo after 12 weeks of treatment (160).

A number of the above and other NHP have been evaluated for their effects on various pre-clinical parameters, biomarkers and surrogate clinical markers involved in the pathogenesis of diabetes and its complications. A discussion of these papers is beyond the scope of this chapter.

7. Adverse Effects

It is important to consider potential harm from the use of NHP. A number of studies of NHP report adverse events, such as gastrointestinal (Fenugreek, Berberine, TM81, bitter melon, oral aloe vera) and dizziness (JYTK). In 1 trial of Tinospora crispa, hepatotoxicity was seen in 2 participants (65). Large doses of Citrullus colocyn can induce diarrhea, but no side effects were reported in the lower doses used in 1 trial (20). Momordica charantia, an NHP commonly used for glycemic control, is an abortifacient (161). Most clinical trials have evaluated small sample sizes over relatively short periods of time and, thus, may not identify all potential side effects or risks.

Some NHP contain pharmaceutical ingredients and/or properties. The Xiaoke Pill contains glibenclamide (glyburide) (11). Nettle has insulin secretagogue, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) and alpha-glucosidase activities. Only NHPs that are properly labelled with a valid natural product number (NPN) should be used to avoid adulteration with unlabelled pharmaceuticals or other contaminants.

Drug-herb interactions may also occur. The most well described is Hypericum perforatum (St. John's wort), which can affect the metabolism of many drugs, including statins, by inducing cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4). Some studies have reported poorer glycemic control in people using glucosamine sulfate for osteoarthritis, but a systematic review concluded that the evidence does not support this concern (162).

8. Other Complementary and Alternative Approaches for the Prevention and Treatment of Diabetes and Its Complications

A number of complementary and alternative approaches have been studied to some degree for diabetes and its complications, others have not. Included here are studies of yoga, traditional Chinese medicine and reflexology. Other modalities of CAM, such as chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation, homeopathy, shiatsu, registered massage therapy or craniosacral therapy do not have studies specific to diabetes.

9. Yoga

The Sanskrit definition of yoga means union or connection. Yoga is a Hindu spiritual discipline. There are many types of yoga, each with its own techniques and methods to awaken greater awareness and connection to self and life. Most practices of yoga include a series of physical postures, breathing and meditation for health, relaxation and overall well-being. Yoga or yoga therapy is often included in a holistic practitioner's (chiropractor, naturopath, osteopath, shiatsu therapist) plan of management for stress reduction and physical strengthening.

Studies of yoga in the management of people with type 2 diabetes show some benefit on glycemic control, lipids and BP, although published studies are generally of short duration with small numbers. In a systematic review and meta-analysis, yoga was found to have positive effects on reducing A1C, as well as fasting and postprandial glucose values (163). There was high heterogeneity among the studies included in the analysis. Other systematic reviews and meta-analyses showed similar improvements in glycemic parameters, as well as improvements in the lipid profile and BP, with similar limitations in the individual studies included (164,165) (see Physical Activity and Diabetes chapter, p. S54). In a meta-analysis of smaller studies looking at comparing the effectiveness of the leisure activities yoga, walking and tai chi on glycemic control in people with type 2 diabetes, yoga with regular frequency (3 times a week) was shown to be more effective than tai chi or walking in lowering A1C levels (166).

10. Traditional Chinese Medicine

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) encompasses a holistic system that includes the combination of herbal medicines, acupuncture, tui na (rigorous massage), dietary therapy, qi gong and tai chi (mind/body techniques combining breathing, movement and mental focus). TCM works within a different paradigm than Western Medicine and, as such, can be difficult to study by Western research techniques. Treatments are complex and focused on individual imbalances detected by pulse and tongue diagnosis rather than specific diseases. Most research on the effectiveness of TCM for people with diabetes is based on specific techniques or Chinese herbal remedies as reviewed above.

Acupuncture is a branch of TCM involving the stimulation of specific points along energy meridians throughout the body to either sedate or tonify the flow of energy. There are various techniques of acupuncture, such as electro and laser acupuncture, and different systems of acupuncture, including scalp and auricular acupuncture. The system and technique most commonly referred to and most often studied refers to the technique of penetrating the skin at specific acupuncture points with thin solid metal needles that are manipulated by the hands.

Acupuncture has not been shown to improve A1C in people with diabetes, with 1 small randomized controlled trial showing it to be no different than placebo on FPG and oral glucose tolerance testing (OGTT) (167). A meta-analysis of acupuncture for diabetic gastroparesis concluded that acupuncture improved some dyspeptic symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite and stomach fullness, with no improvement in solid gastric emptying (168). A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of manual acupuncture for the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy reported that manual acupuncture had a better effect on global symptom improvement compared with vitamin B12 or no treatment, and that the combination of manual acupuncture and vitamin B12 had a better effect compared with vitamin B12 alone. However, the authors could not draw clinically relevant conclusions because of high risks of bias in the studies included (169).

Tai chi is an ancient mind and body practice involving gentle, slow, continuous body movements with mental focus, breathing and relaxation. Although there may be some benefit in quality of life, there is little evidence for benefit of tai chi on glycemic control in diabetes (170,171).

11. Manual Therapies

There is a growing number of people with diabetes who seek care for musculoskeletal complaints and overall lifestyle management from natural and/or complementary medicine practitioners. Manual therapies, including chiropractic, physiotherapy, shiatsu, registered massage therapy and craniosacral therapy have no randomized controlled trial data in people with diabetes. A few small studies on tactile massage, a superficial gentle form of massage, have failed to demonstrate a significant beneficial effect on A1C (172–174). Reflexology is a system of massage based on the theory that reflex points on the feet, hands and head are linked to other internal parts of the body. In a small, open-label, randomized controlled trial in people with diabetic peripheral neuropathy, foot reflexology was shown to reduce A1C and FPG, and improve pain scores and nerve conduction velocity (175).

12. Other Relevant Guidelines

- Physical Activity and Diabetes, p. S54

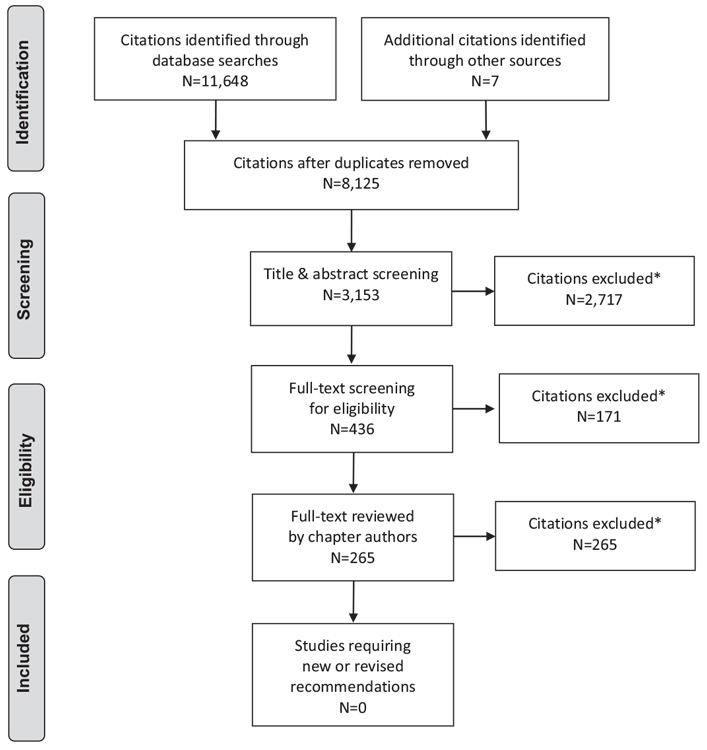

Literature Review Flow Diagram for Chapter 22: Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Diabetes

*Excluded based on: population, intervention/exposure, comparator/control or study design.

From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(6): e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097 (176).

For more information, visit www.prisma-statement.org.

13. Author Disclosures

Dr. Grossman reports grants and personal fees from Novo Nordisk, Janssen, and Eli Lilly; grants from Merck, Takeda, Sanofi, AstraZeneca, and Lexicon, outside the submitted work; and previous employee (now retired) of Eli Lilly Canada. No other authors have anything to disclose.

Recommendations

- Health-care providers should ask about the use of complementary and alternative medicine in people with diabetes [Grade D, Consensus].

- There is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation regarding efficacy and safety of complementary or alternative medicine for individuals with diabetes [Grade D, Consensus].

Abbreviations:

A1C, glycated hemoglobin; ALA, alpha linoleic acid; BP, blood pressure; CAM, complementary or alternative medicine; CV, cardiovascular; CVD, cardiovascular disease; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MI, myocardial infarct; NCS, nerve conduction studies; NHP, natural health product; NPN, natural product number; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; TCM, traditional Chinese medicine; TG, triglycerides, UAE, urinary albumin excretion.

References

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: What’s in a name? Bethesda: National Institue of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016. https://nccih.nih.gov/health/integrative-health.

- Esmail N. Complementary and alternative medicine: Use and public attitudes 1997, 2006, and 2016. Vancouver: Fraser Institue, 2017. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/complementary-and-alternative-medicine-2017.pdf.

- Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, et al. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. Natl Health Stat Report 2015;1–16.

- Ryan EA, Pick ME, Marceau C. Use of alternative medicines in diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med 2001;18:242–5.

- Yeh GY, Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among persons with diabetes mellitus: Results of a national survey. Am J Public Health 2002;92:1648–52.

- Egede LE, Ye X, Zheng D, et al. The prevalence and pattern of complementary and alternative medicine use in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002;25:324–9.

- Tan AC, Mak JC. Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Diabetes (CALMIND)—a prospective study. J Complement Integr Med 2015;12:95–9.

- Non-prescription Health Products Directorate (NNHPD). What are natural health products. Ottawa: Health Canada, 2004. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/prodnatur/index-eng.php.

- Saper RB, Kales SN, Paquin J, et al. Heavy metal content of ayurvedic herbal medicine products. JAMA 2004;292:2868–73.

- Dick WR, Fletcher EA, Shah SA. Reduction of fasting blood glucose and hemoglobin A1c using oral aloe vera: A meta-analysis. J Altern Complement Med 2016;22:450–7.

- Ji L, Tong X, Wang H, et al. Efficacy and safety of traditional chinese medicine for diabetes: A double-blind, randomised, controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e56703.

- Treiber G, Prietl B, Fröhlich-Reiterer E, et al. Cholecalciferol supplementation improves suppressive capacity of regulatory T-cells in young patients with newonset type 1 diabetes mellitus—a randomized clinical trial. Clin Immunol 2015;161:217–24.

- Khan H, Kunutsor S, Franco OH, et al. Vitamin D, type 2 diabetes and other metabolic outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Proc Nutr Soc 2013;72:89–97.

- Lim S, Kim MJ, Choi SH, et al. Association of vitamin D deficiency with incidence of type 2 diabetes in high-risk Asian subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;97:524–30.

- Uusitalo U, Liu X, Yang J, et al. Association of early exposure of probiotics and islet autoimmunity in the TEDDY study. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170:20–8.

- Lian F, Li G, Chen X, et al. Chinese herbal medicine Tianqi reduces progression from impaired glucose tolerance to diabetes: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99(2):648–55.

- Muley A, Muley P, Shah M. ALA, fatty fish or marine n-3 fatty acids for preventing DM?: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Diabetes Rev 2014;10:158–65.

- Fang Z, Zhao J, Shi G, et al. Shenzhu Tiaopi granule combined with lifestyle intervention therapy for impaired glucose tolerance: A randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med 2014;22:842–50.

- Awasthi H, Nath R, Usman K, et al. Effects of a standardized Ayurvedic formulation on diabetes control in newly diagnosed type-2 diabetics; a randomized active controlled clinical study. Complement Ther Med 2015;23:555–61.

- Huseini HF, Darvishzadeh F, Heshmat R, et al. The clinical investigation of Citrullus colocynthis (L.) schrad fruit in treatment of type II diabetic patients: A randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Phytother Res 2009;23:1186–9.

- Kuriyan R, Rajendran R, Bantwal G, et al. Effect of supplementation of Coccinia cordifolia extract on newly detected diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2008;31:216–20.

- Sarbolouki S, Javanbakht MH, Derakhshanian H, et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid improves insulin sensitivity and blood sugar in overweight type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: A double-blind randomised clinical trial. Singapore Med J 2013;54:387–90.

- Gao Y, Lan J, Dai X, et al. A phase I/II study of Ling Zhi mushroom Ganoderma lucidum (W.Curt.:Fr.) Lloyd (Aphyllophoromycetidae) extract in patients with type 2 diabetes. Int J Med Mushrooms 2004;6:33–9.

- Shidfar F, Rajab A, Rahideh T, et al. The effect of ginger (Zingiber officinale) on glycemic markers in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Complement Integr Med 2015;12:165–70.

- Huyen VT, Phan DV, Thang P, et al. Antidiabetic effect of Gynostemma pentaphyllum tea in randomly assigned type 2 diabetic patients. Horm Metab Res 2010;42:353–7.

- Korecova M, Hladikova M. Treatment of mild and moderate type-2 diabetes: Open prospective trial with hintonia latiflora extract. Eur J Med Res 2014;19:16.

- Kershengolts BM, Sydykova LA, Sharoyko VV, et al. Lichens’ B-Oligosaccharides in the correction of metabolic disorders in type 2 diabetes Mellitus. Wiad Lek 2015;68:480–2.

- Zhu CF, Li GZ, Peng HB, et al. Treatment with marine collagen peptides modulates glucose and lipid metabolism in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2010;35:797–804.

- Kianbakht S, Khalighi-Sigaroodi F, Dabaghian FH. Improved glycemic control in patients with advanced type 2 diabetes mellitus taking Urtica dioica leaf extract: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin Lab 2013;59:1071–6.

- Hariharan RS, Vankataraman S, Sunitha P, et al. Efficacy of vijayasar (Pterocarpus marsupium) in the treatment of newly diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A flexible dose double-blind multicenter randomized controlled trial. Diabetol Croat 2005;34:13–20. http://www.idb.hr/diabetologia/05no1-2.pdf.

- Jayawardena MH, de Alwis NM, Hettigoda V, et al. A double blind randomised placebo controlled cross over study of a herbal preparation containing Salacia reticulata in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. J Ethnopharmacol 2005;97:215–18.

- Senadheera SP, Ekanayake S, Wanigatunge C. Anti-hyperglycaemic effects of herbal porridge made of Scoparia dulcis leaf extract in diabetics—a randomized crossover clinical trial. BMC Complement Altern Med 2015;15:410.

- Hussain SA. Silymarin as an adjunct to glibenclamide therapy improves longterm and postprandial glycemic control and body mass index in type 2 diabetes. J Med Food 2007;10:543–7.

- Huseini HF, Larijani B, Heshmat R, et al. The efficacy of Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn. (silymarin) in the treatment of type II diabetes: A randomized, doubleblind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial. Phytother Res 2006;20:1036–9.

- Kang MJ, Kim JI, Yoon SY, et al. Pinitol fromsoybeans reduces postprandial blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Med Food 2006;9:182–6.

- Fujita H, Yamagami T, Ohshima K. Long-term ingestion of a fermented soybeanderived Touchi-extract with alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activity is safe and effective in humans with borderline and mild type-2 diabetes. J Nutr 2001;131:2105–8.

- Lan J, Zhao Y, Dong F, et al. Meta-analysis of the effect and safety of berberine in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hyperlipemia and hypertension. J Ethnopharmacol 2015;161:69–81.

- Tu X, Xie C, Wang F, et al. Fructus mume formula in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomized controlled pilot trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013;2013:787459.

- Xu J, Lian F, Zhao L, et al. Structural modulation of gut microbiota during alleviation of type 2 diabetes with a Chinese herbal formula. ISME J 2015;9:552–62.

- Hu Y, Zhou X, Guo DH, et al. Effect of JYTK on antioxidant status and inflammation in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized double-blind clinical trial. Int J Endocrinol Metab 2016;14:e34400.

- Lian F, Tian J, Chen X, et al. The efficacy and safety of chinese herbal medicine jinlida as add-on medication in type 2 diabetes patients ineffectively managed by metformin monotherapy: A double-blind, randomized, placebocontrolled, multicenter trial. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0130550.

- Qiang G, Wenzhai C, Huan Z, et al. Effect of Sancaijiangtang on plasma nitric oxide and endothelin-1 levels in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and vascular dementia: A single-blind randomized controlled trial. J Tradit Chin Med 2015;35:375–80.

- Zhang X, Liu Y, Xiong D, et al. Insulin combined with Chinese medicine improves glycemic outcome through multiple pathways in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig 2015;6:708–15.

- Tong XL,Wu ST, Lian FM, et al. The safety and effectiveness of TM81, a Chinese herbal medicine, in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: A randomized doubleblind placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab 2013;15:448–54.

- Ma J, Xu L, Dong J, et al. Effects of zishentongluo in patients with early-stage diabetic nephropathy. Am J Chin Med 2013;41:333–40.

- Lu FR, Shen L, Qin Y, et al. Clinical observation on trigonella foenum-graecum L. total saponins in combination with sulfonylureas in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Chin J Integr Med 2008;14:56–60.

- Neelakantan N, Narayanan M, de Souza RJ, et al. Effect of fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.) intake on glycemia: A meta-analysis of clinical trials. Nutr J 2014;13:7.

- Hsu CH, Liao YL, Lin SC, et al. The mushroom Agaricus Blazei Murill in combination with metformin and gliclazide improves insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes: A randomized, double-blinded, and placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Altern Complement Med 2007;13:97–102.

- Mucalo I, Jovanovski E, Rahelic´ D, et al. Effect of American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius L.) on arterial stiffness in subjects with type-2 diabetes and concomitant hypertension. J Ethnopharmacol 2013;150:148–53.

- Rytter E, Vessby B, Asgard R, et al. Supplementation with a combination of antioxidants does not affect glycaemic control, oxidative stress or inflammation in type 2 diabetes subjects. Free Radic Res 2010;44:1445–53.

- Fenercioglu AK, Saler T, Genc E, et al. The effects of polyphenol-containing antioxidants on oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation in type 2 diabetes mellitus without complications. J Endocrinol Invest 2010;33:118–24.

- Mackenzie T, Leary L, Brooks WB. The effect of an extract of green and black tea on glucose control in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Double-blind randomized study. Metabolism 2007;56:1340–4.

- Barre DE, Mizier-Barre KA, Griscti O, et al. High dose flaxseed oil supplementation may affect fasting blood serum glucose management in human type 2 diabetics. J Oleo Sci 2008;57:269–73.

- Liu X,Wei J, Tan F, et al. Antidiabetic effect of Pycnogenol Frenchmaritime pine bark extract in patients with diabetes type II. Life Sci 2004;75:2505–13.

- Gui QF, Xu ZR, Xu KY, et al. The efficacy of ginseng-related therapies in type 2 diabetes mellitus: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e2584.

- Shishtar E, Sievenpiper JL, Djedovic V, et al. The effect of ginseng (the genus panax) on glycemic control: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e107391.

- Hosseini S, Jamshidi L, Mehrzadi S, et al. Effects of Juglans regia L. leaf extract on hyperglycemia and lipid profiles in type two diabetic patients: A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Ethnopharmacol 2014;152: 451–6.

- Pu R, Geng XN, Yu F, et al. Liuwei dihuang pills enhance the effect of Western medicine in treating type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Chin J Integr Med 2013;19:783–91.

- Dans AM, Villarruz MV, Jimeno CA, et al. The effect of Momordica charantia capsule preparation on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus needs further studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2007;60:554–9.

- Yin RV, Lee NC, Hirpara H, et al. The effect of bitter melon (Mormordica charantia) in patients with diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Nutr Diabetes 2014;4:e145.

- Hashem Dabaghian F, AbdollahifardM, Khalighi Sigarudi F, et al. Effects of Rosa canina L. fruit on glycemia and lipid profile in type 2 diabetic patients: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Med Plants 2015;14:95–104.

- Behradmanesh S, Derees F, Rafieian-Kopaei M. Effect of salvia officinalis on diabetic patients. J Renal Inj Prev 2013;2:51–4.

- Jayagopal V, Albertazzi P, Kilpatrick ES, et al. Beneficial effects of soy phytoestrogen intake in postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002;25:1709–14.

- Kumar V, Mahdi F, Singh R, et al. A clinical trial to assess the antidiabetic, antidyslipidemic and antioxidant activities of Tinospora cordifolia in management of type - 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Pharm Sci Res 2016;7:757–64. http://ijpsr.com/bft-article/a-clinical-trial-to-assess-the-antidiabetic-antidyslipidemic-and-antioxidant-activities-of-tinospora-cordifolia-in-management-of-type-2-diabetes-mellitus/?view=fulltext.

- Sangsuwan C, Udompanthurak S, Vannasaeng S, et al. Randomized controlled trial of Tinospora crispa for additional therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Med Assoc Thai 2004;87:543–6.

- Chen H, Karne RJ, Hall G, et al. High-dose oral vitamin C partially replenishes vitamin C levels in patients with type 2 diabetes and low vitamin C levels but does not improve endothelial dysfunction or insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2006;290:H137–45.

- Bhatt JK, Thomas S, Nanjan MJ. Effect of oral supplementation of vitamin C on glycemic control and lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci 2012;4:524–7.

- Tabatabaei-Malazy O, Nikfar S, Larijani B, et al. Influence of ascorbic acid supplementation on type 2 diabetes mellitus in observational and randomized controlled trials; a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Pharm Pharm Sci 2014;17:554–82.

- Lonn E, Yusuf S, Hoogwerf B, et al. Effects of vitamin E on cardiovascular and microvascular outcomes in high-risk patients with diabetes: Results of the HOPE study and MICRO-HOPE substudy. Diabetes Care 2002;25:1919–27.

- Boshtam M, Rafiei M, Golshadi ID, et al. Long term effects of oral vitamin E supplement in type II diabetic patients. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 2005;75:341–6.

- Suksomboon N, Poolsup N, Sinprasert S. Effects of vitamin E supplementation on glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Pharm Ther 2011;36:53–63.

- Udupa A, Nahar P, Shah S, et al. A comparative study of effects of omega-3 fatty acids, alpha lipoic acid and vitamin e in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Med Health Sci Res 2013;3:442–6.

- Xu R, Zhang S, Tao A, et al. Influence of vitamin E supplementation on glycaemic control: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e95008.

- Mang B, Wolters M, Schmitt B, et al. Effects of a cinnamon extract on plasma glucose, HbA, and serum lipids in diabetes mellitus type 2. Eur J Clin Invest 2006;36:340–4.

- Blevins SM, Leyva MJ, Brown J, et al. Effect of cinnamon on glucose and lipid levels in non insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007;30:2236–7.

- Crawford P. Effectiveness of cinnamon for lowering hemoglobin A1C in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized, controlled trial. J Am Board Fam Med 2009;22:507–12.

- Akilen R, Tsiami A, Devendra D, et al. Glycated haemoglobin and blood pressurelowering effect of cinnamon in multi-ethnic type 2 diabetic patients in the UK: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Diabet Med 2010;27:1159–67.

- Suppapitiporn S, Kanpaksi N, Suppapitiporn S. The effect of cinnamon cassia powder in type 2 diabetes mellitus. JMed Assoc Thai 2006;89(Suppl. 3):S200–5.

- Allen RW, Schwartzman E, Baker WL, et al. Cinnamon use in type 2 diabetes: An updated systematic reviewand meta-analysis. Ann FamMed 2013;11:452–9.

- Eriksson JG, Forsen TJ, Mortensen SA, et al. The effect of coenzyme Q10 administration on metabolic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biofactors 1999;9:315–18.

- Kolahdouz Mohammadi R, Hosseinzadeh-Attar MJ, Eshraghian MR, et al. The effect of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on metabolic status of type 2 diabetic patients. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol 2013;59:231–6.

- Suksomboon N, Poolsup N, Juanak N. Effects of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on metabolic profile in diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Pharm Ther 2015;40:413–18.

- Zahedi H, Eghtesadi S, Seifirad S, et al. Effects of CoQ10 supplementation on lipid profiles and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Diabetes Metab Disord 2014;13:81.

- Suksomboon N, Poolsup N, Yuwanakorn A. Systematic review and metaanalysis of the efficacy and safety of chromium supplementation in diabetes. J Clin Pharm Ther 2014;39:292–306.

- Akbari Fakhrabadi M, Zeinali Ghotrom A, Mozaffari-Khosravi H, et al. Effect of coenzyme Q10 on oxidative stress, glycemic control and inflammation in diabetic neuropathy: A double blind randomized clinical trial. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 2014;84:252–60.

- Moradi M, Haghighatdoost F, Feizi A, et al. Effect of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on diabetes biomarkers: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Arch Iran Med 2016;19:588–96.

- Ludvik B, Neuffer B, Pacini G. Efficacy of Ipomoea batatas (Caiapo) on diabetes control in type 2 diabetic subjects treated with diet. Diabetes Care 2004;27:436–40.

- Ludvik B, Hanefeld M, Pacini G. Improved metabolic control by Ipomoea batatas (Caiapo) is associated with increased adiponectin and decreased fibrinogen levels in type 2 diabetic subjects. Diabetes Obes Metab 2008;10:586–92.

- Derosa G, Cicero AF, Gaddi A, et al. The effect of L-carnitine on plasma lipoprotein(a) levels in hypercholesterolemic patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Ther 2003;25:1429–39.

- Rahbar AR, Shakerhosseini R, Saadat N, et al. Effect of L-carnitine on plasma glycemic and lipidemic profile in patients with type II diabetes mellitus. Eur J Clin Nutr 2005;59:592–6.

- Derosa G, Maffioli P, Ferrari I, et al. Orlistat and L-carnitine compared to orlistat alone on insulin resistance in obese diabetic patients. Endocr J 2010;57:777–86.

- Derosa G, Maffioli P, Salvadeo SA, et al. Sibutramine and L-carnitine compared to sibutramine alone on insulin resistance in diabetic patients. Intern Med 2010;49:1717–25.

- Rodriguez-Moran M, Guerrero-Romero F. Oral magnesium supplementation improves insulin sensitivity and metabolic control in type 2 diabetic subjects: A randomized double-blind controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2003;26:1147–52.

- de Valk HW, Verkaaik R, van Rijn HJ, et al. Oral magnesium supplementation in insulin-requiring type 2 diabetic patients. Diabet Med 1998;15:503–7.

- Eibl NL, Kopp HP, Nowak HR, et al. Hypomagnesemia in type II diabetes: Effect of a 3-month replacement therapy. Diabetes Care 1995;18:188–92.

- Eriksson J, Kohvakka A. Magnesium and ascorbic acid supplementation in diabetes mellitus. Ann Nutr Metab 1995;39:217–23.

- Song Y, He K, Levitan EB, et al. Effects of oral magnesium supplementation on glycaemic control in Type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of randomized doubleblind controlled trials. Diabet Med 2006;23:1050–6.

- Navarrete-Cortes A, Ble-Castillo JL, Guerrero-Romero F, et al. No effect of magnesium supplementation on metabolic control and insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetic patients with normomagnesemia. Magnes Res 2014;27:48–56.

- Solati M, Ouspid E, Hosseini S, et al. Oral magnesium supplementation in type II diabetic patients. Med J Islam Repub Iran 2014;28:67.

- Veleba J, Kopecky J Jr, Janovska P, et al. Combined intervention with pioglitazone and n-3 fatty acids in metformin-treated type 2 diabetic patients: Improvement of lipid metabolism. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2015;12:52–67.

- Chen C, Yu X, Shao S. Effects of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation on glucose control and lipid levels in type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0139565.

- Zhang Q, Wu Y, Fei X. Effect of probiotics on glucose metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicina (Kaunas) 2016;52:28–34.

- Razmpoosh E, Javadi M, Ejtahed HS, et al. Probiotics as beneficial agents in the management of diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2016;32:143–68.

- Capdor J, Foster M, Petocz P, et al. Zinc and glycemic control: A meta-analysis of randomised placebo controlled supplementation trials in humans. J Trace Elem Med Biol 2013;27:137–42.

- Jayawardena R, Ranasinghe P, Galappatthy P, et al. Effects of zinc supplementation on diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2012;4:13.

- Landman GW, Bilo HJ, Houweling ST, et al. Chromium does not belong in the diabetes treatment arsenal: Current evidence and future perspectives. World J Diabetes 2014;5:160–4.

- Lewicki S, Zdanowski R, Krzyzowska M, et al. The role of Chromium III in the organism and its possible use in diabetes and obesity treatment. Ann Agric Environ Med 2014;21:331–5.

- McIver DJ, Grizales AM, Brownstein JS, et al. Risk of type 2 diabetes Is lower in US adults taking chromium-containing supplements. J Nutr 2015;145:2675–82.

- Althuis MD, Jordan NE, Ludington EA, et al. Glucose and insulin responses to dietary chromium supplements: Ameta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2002;76:148–55.

- Martin J, Wang ZQ, Zhang XH, et al. Chromium picolinate supplementation attenuates body weight gain and increases insulin sensitivity in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006;29:1826–32.

- Kleefstra N, Houweling ST, Jansman FG, et al. Chromium treatment has no effect in patients with poorly controlled, insulin-treated type 2 diabetes in an obese Western population: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2006;29:521–5.

- Ghosh D, Bhattacharya B, Mukherjee B, et al. Role of chromium supplementation in Indians with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Nutr Biochem 2002;13:690– 7.

- Anderson RA, Roussel AM, Zouari N, et al. Potential antioxidant effects of zinc and chromium supplementation in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Nutr 2001;20:212–18.

- Anderson RA, Cheng N, Bryden NA, et al. Elevated intakes of supplemental chromium improve glucose and insulin variables in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 1997;46:1786–91.

- Kleefstra N, Houweling ST, Bakker SJ, et al. Chromium treatment has no effect in patients with type 2 diabetes in aWestern population: A randomized, doubleblind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2007;30:1092–6.

- Balk EM, Tatsioni A, Lichtenstein AH, et al. Effect of chromium supplementation on glucose metabolism and lipids: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care 2007;30:2154–63.

- Albarracin CA, Fuqua BC, Evans JL, et al. Chromium picolinate and biotin combination improves glucose metabolism in treated, uncontrolled overweight to obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2008;24:41–51.

- Albarracin C, Fuqua B, Geohas J, et al. Combination of chromium and biotin improves coronary risk factors in hypercholesterolemic type 2 diabetes mellitus: A placebo-controlled, double-blind randomized clinical trial. J Cardiometab Syndr 2007;2:91–7.

- Lai MH. Antioxidant effects and insulin resistance improvement of chromium combined with vitamin C and e supplementation for type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Biochem Nutr 2008;43:191–8.

- Abdollahi M, Farshchi A, Nikfar S, et al. Effect of chromium on glucose and lipid profiles in patients with type 2 diabetes; a meta-analysis review of randomized trials. J Pharm Pharm Sci 2013;16:99–114.

- Paiva AN, Lima JG, Medeiros AC, et al. Beneficial effects of oral chromium picolinate supplementation on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized clinical study. J Trace Elem Med Biol 2015;32:66–72.

- Yin RV, Phung OJ. Effect of chromium supplementation on glycated hemoglobin and fasting plasma glucose in patients with diabetes mellitus. Nutr J2015;14:14.

- Witham MD, Dove FJ, Dryburgh M, et al. The effect of different doses of vitamin D(3) on markers of vascular health in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 2010;53:2112–19.

- Patel P, Poretsky L, Liao E. Lack of effect of subtherapeutic vitamin D treatment on glycemic and lipid parameters in type 2 diabetes: A pilot prospective randomized trial. J Diabetes 2010;2:36–40.

- Jorde R, Figenschau Y. Supplementation with cholecalciferol does not improve glycaemic control in diabetic subjects with normal serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. Eur J Nutr 2009;48:349–54.

- Nasri H, Behradmanesh S, Maghsoudi AR, et al. Efficacy of supplementary vitamin D on improvement of glycemic parameters in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus; a randomized double blind clinical trial. J Renal Inj Prev 2014;3:31–4.

- Nigil Haroon N, Anton A, John J, et al. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review of interventional studies. J Diabetes Metab Disord 2015;14:3.

- Forouhi NG, Menon RK, Sharp SJ, et al. Effects of vitamin D2 or D3 supplementation on glycaemic control and cardiometabolic risk among people at risk of type 2 diabetes: Results of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab 2016;18:392–400.

- Ghavamzadeh S, Mobasseri M, Mahdavi R. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on adiposity, blood glycated hemoglobin, serum leptin and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in type 2 diabetic patients. Int J Prev Med 2014;5:1091–8.

- Krul-Poel YH, Westra S, ten Boekel E, et al. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes (SUNNY trial): A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2015;38:1420–6.

- Nwosu BU, Maranda L. The effects of vitamin D supplementation on hepatic dysfunction, vitamin D status, and glycemic control in children and adolescents with vitamin D deficiency and either type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e99646.

- Elkassaby S, Harrison LC, Mazzitelli N, et al. A randomised controlled trial of high dose vitamin D in recent-onset type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2014;106:576–82.

- Strobel F, Reusch J, Penna-Martinez M, et al. Effect of a randomised controlled vitamin D trial on insulin resistance and glucose metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Horm Metab Res 2014;46:54–8.

- Jehle S, Lardi A, Felix B, et al. Effect of large doses of parenteral vitamin D on glycaemic control and calcium/phosphate metabolism in patients with stable type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomised, placebo-controlled, prospective pilot study. Swiss Med Wkly 2014;144:w13942.

- Ryu OH, Lee S, Yu J, et al. A prospective randomized controlled trial of the effects of vitamin D supplementation on long-term glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus of Korea. Endocr J 2014;61:167–76.

- Al-Sofiani ME, Jammah A, Racz M, et al. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on glucose control and inflammatory response in type II diabetes: A double blind, randomized clinical trial. Int J Endocrinol Metab 2015;13:e22604.

- Autier P, Boniol M, Pizot C, et al. Vitamin D status and ill health: A systematic review. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2:76–89.

- Breslavsky A, Frand J, Matas Z, et al. Effect of high doses of vitamin D on arterial properties, adiponectin, leptin and glucose homeostasis in type 2 diabetic patients. Clin Nutr 2013;32:970–5.

- Seida JC, Mitri J, Colmers IN, et al. Clinical review: Effect of vitamin D3 supplementation on improving glucose homeostasis and preventing diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99:3551–60.

- Papandreou D, Hamid ZT. The role of vitamin D in diabetes and cardiovascular disease: An updated review of the literature. Dis Markers 2015;2015: 580474.

- Munoz-Aguirre P, Flores M, Macias N, et al. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on serum lipids in postmenopausal women with diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Nutr 2015;34:799–804.

- Jafari T, Fallah AA, Barani A. Effects of vitamin D on serum lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes: Ameta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Nutr 2016;35:1259–68.

- Eftekhari MH, Akbarzadeh M, Dabbaghmanesh MH, et al. The effect of calcitriol on lipid profile and oxidative stress in hyperlipidemic patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arya Atheroscler 2014;10:82–8.

- Wainstein J, Landau Z, Bar Dayan Y, et al. Purslane extract and glucose homeostasis in adults with type 2 diabetes: A double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of efficacy and safety. J Med Food 2016;19:133–40.

- Lee KJ, Lee YJ. Effects of vitamin D on blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2016;54:233–42.

- Lamas GA, Goertz C, Boineau R, et al. Effect of disodium EDTA chelation regimen on cardiovascular events in patients with previous myocardial infarction: The TACT randomized trial. JAMA 2013;309:1241–50.

- Escolar E, Lamas GA, Mark DB, et al. The Effect of an EDTA-based chelation regimen on patients with diabetes mellitus and prior myocardial infarction in the Trial to Assess Chelation Therapy (TACT). Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2014;7:15–24.

- Lian F,Wu L, Tian J, et al. The effectiveness and safety of a danshen-containing Chinese herbal medicine for diabetic retinopathy: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter clinical trial. J Ethnopharmacol 2015;164:71–7.

- Ou JY, Huang D,Wu YS, et al. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of yiqi yangyin huoxue method in treating diabetic nephropathy. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2016;2016:3257603.

- Xiang L, Jiang P, Zhou L, et al. Additive effect of qidan dihuang grain, a traditional Chinese medicine, and angiotensin receptor blockers on albuminuria levels in patients with diabetic nephropathy: A randomized, parallel-controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2016;2016:1064924.

- Liu H, Zheng J, Li RH. Clinical efficacy of “Spleen-kidney-care” Yiqi Huayu and Jiangzhuo traditional Chinese medicine for the treatment of patients with diabetic nephropathy. Exp Ther Med 2015;10:1096–102.

- Chen YZ, Gong ZX, Cai GY, et al. Efficacy and safety of Flos Abelmoschus manihot (Malvaceae) on type 2 diabetic nephropathy: A systematic review. Chin J Integr Med 2015;21:464–72.

- Yang G, Zhang M, Zhang M, et al. Effect of Huangshukuihua (Flos Abelmoschi Manihot) on diabetic nephropathy: A meta-analysis. J Tradit Chin Med 2015;35:15–20.

- Wang B, Chen S, Yan X, et al. The therapeutic effect and possible harm of puerarin for treatment of stage III diabetic nephropathy: Ameta-analysis. Altern Ther Health Med 2015;21:36–44.

- Li P, Chen Y, Liu J, et al. Efficacy and safety of tangshen formula on patients with type 2 diabetic kidney disease: A multicenter double-blinded randomized placebo-controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0126027.

- Zhao JY, Dong JJ, Wang HP, et al. Efficacy and safety of vitamin D3 in patients with diabetic nephropathy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Chin Med J 2014;127:2837–43.

- Joergensen C, Tarnow L, Goetze JP, et al. Vitamin D analogue therapy, cardiovascular risk and kidney function in people with type 1 diabetes mellitus and diabetic nephropathy: A randomized trial. Diabet Med 2015;32:374–81.

- Heydari M, Homayouni K, Hashempur MH, et al. Topical citrullus colocynthis (bitter apple) extract oil in painful diabetic neuropathy: A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Diabetes 2016;8:246–52.

- Wu J, Zhang X, Zhang B. Efficacy and safety of puerarin injection in treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. J Tradit Chin Med 2014;34:401–10.

- Tsai CI, Li TC, Chang MH, et al. Chinese medicinal formula (MHGWT) for relieving diabetic neuropathic pain: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013;2013.

- Krawinkel MB, Keding GB. Bitter gourd (Momordica Charantia): A dietary approach to hyperglycemia. Nutr Rev 2006;64:331–7.

- Simon RR, Marks V, Leeds AR, et al. A comprehensive review of oral glucosamine use and effects on glucose metabolism in normal and diabetic individuals. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2011;27:14–27.

- Kumar V, Jagannathan A, Philip M, et al. Role of yoga for patients with type II diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med 2016;25:104–12.

- Innes KE, Selfe TK. Yoga for adults with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review of controlled trials. J Diabetes Res 2016;2016:6979370.

- de G R Hansen E, Innes KE. The benefits of yoga for adults with type 2 diabetes: A review of the evidence and call for a collaborative, integrated research initiative. Int J Yoga Therap 2013;71–83.

- Pai LW, Li TC, Hwu YJ, et al. The effectiveness of regular leisure-time physical activities on long-term glycemic control in people with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2016;113:77–85.

- Tjipto BW, Saputra K, Sutrisno TC. Effectiveness of acupuncture as an adjunctive therapy for diabetes mellitus: A randomized controlled trial.Med Acupunct 2014;26:341–5.

- Yang M, Li X, Liu S, et al. Meta-analysis of acupuncture for relieving nonorganic dyspeptic symptoms suggestive of diabetic gastroparesis. BMC Complement Altern Med 2013;13:311.

- Chen W, Yang GY, Liu B, et al. Manual acupuncture for treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e73764.

- Lee MS, Jun JH, Lim HJ, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of tai chi for treating type 2 diabetes. Maturitas 2015;80:14–23.

- Yan JH, Gu WJ, Pan L. Lack of evidence on Tai Chi-related effects in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2013;121:266–71.

- Wändell PE, Ärnlöv J, Nixon Andreasson A, et al. Effects of tactile massage on metabolic biomarkers in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab 2013;39:411–17.

- Andersson K, Wändell P, Törnkvist L. Tactile massage improves glycaemic control in women with type 2 diabetes: A pilot study. Pract Diabetes Int 2004;21:105–9.

- Wändell PE, Carlsson AC, Andersson K, et al. Tactile massage or relaxation exercises do not improve the metabolic control of type 2 diabetics. Open Diabetes J 2010;3:6–10.

- Dalal K, Maran VB, Pandey RM, et al. Determination of efficacy of reflexology in managing patients with diabetic neuropathy: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2014;2014:843036.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097.